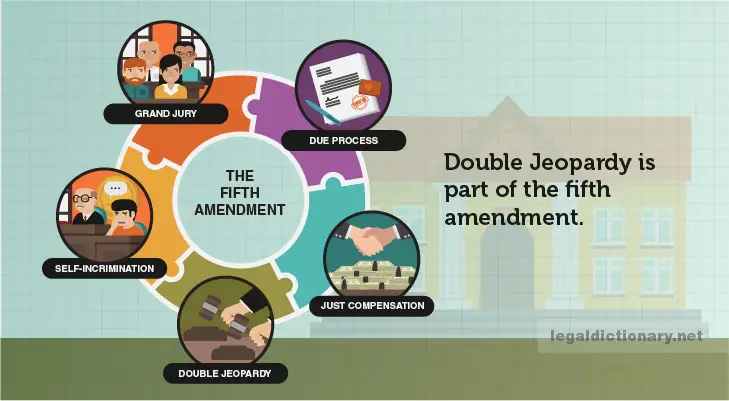

Double jeopardy protects people from being tried for the same crime twice in a court of law. The clause is found in the Fifth Amendment of the United States Constitution, where it was included to prevent the government from erroneously or maliciously convicting innocent people, and to protect people from the consequences of successive prosecutions. It also helps to preserve the finality of criminal proceedings. To explore this concept, consider the following double jeopardy definition.

Origin

Legal principal of double jeopardy law was stated in the Fifth Amendment, which was ratified in 1791. The term “double jeopardy” was first used about 1905.

Double jeopardy law only applies to criminal court cases and does not protect people from being brought back to trial in civil proceedings. This means that if a person is found not guilty of manslaughter, he cannot be tried in criminal court again. However, the family of the slain victim can sue the defendant in civil court for a wrongful death suit to recover damages.

Most criminal cases are eligible for double jeopardy protection, primarily because criminal conviction may result in loss of liberty or life. The Fifth Amendment extends double jeopardy protection to those proceedings that threaten a person’s “life or limb.” However, the Supreme Court has established that eligibility for double jeopardy protection is not limited to capital crimes, but encompasses all felonies, misdemeanors, and juvenile convictions, regardless of the punishment that may be handed down. In modern times, this protection is extended because criminal conviction may result in loss of “liberty.”

The 1969 case Benton v Maryland set a precedent stating that double jeopardy law extends to both state and federal criminal cases. Prior to this U.S. Supreme Court ruling, the double jeopardy clause of the Constitution only protected defendants facing federal charges, unless the state’s statutes provided a similar clause. Some states offered a greater range of double jeopardy protection than others, but most often, the level of protection against successive prosecution was much less than what was offered at the federal level. The Supreme Court held that every state must offer the same level of protection for the double jeopardy clause afforded by the federal government.

Double Jeopardy attaches, or becomes effective, once the jury is sworn in or, in cases in which the defendant chooses a bench trial rather than a jury trial, when the first witness is sworn in. If the defendant agrees to a plea deal, attachment of double jeopardy does not occur until the court formally accepts the plea agreement.

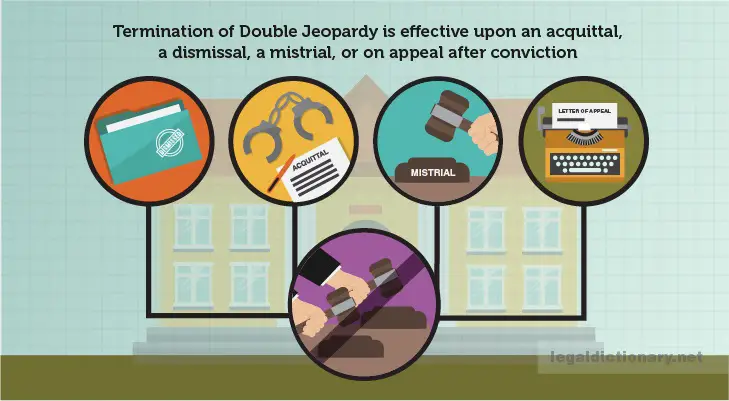

Understanding termination of Double Jeopardy is a little more complicated than knowing when it begins, and is at least as important. This is because, once jeopardy has terminated, the individual cannot be detained to face additional proceedings on the same matter. Termination of double jeopardy occurs in any of four circumstances: (1) upon acquittal, (2) upon dismissal, (3) after a mistrial, or (4) on appeal after conviction. However, with nearly all of these prohibitions, there are certain circumstances that arise where double jeopardy is not terminated.

When a jury issues a verdict of acquittal, the verdict cannot be overturned on appeal for any reason, and so double jeopardy is terminated after acquittal. The jury also has the option of implicitly acquitting a defendant. This is done by returning a guilty verdict on a lesser offense, and not addressing, or remaining silent on the greater offense. In this instance, the defendant cannot be retried for the greater offense as the jury’s silence is interpreted by the court as a verdict of not guilty.

Blockburger v United States

In the 1932 case of Blockburger v United States, the defendant had been indicted on five separate counts of drug trafficking, all of which involved the sale of morphine to a single purchaser. The jury found the defendant guilty only on counts two, three, and five. Count two charged the defendant with the sale of ten grains of morphine not in the original form or package; count three involved the sale of eight grains of morphine not in the original form or packaging on a different day; and the sale in count five did not involve a written order. The defendant was sentenced to serve five years in prison for each conviction, to be served consecutively.

The defendant appealed the conviction, claiming that, because all of the sales were made to the same person, they should count as only one charge. The appellate judge upheld the trial court’s convictions, saying that, since the sales in counts two and three occurred at different times, they were two different crimes, and could be punished as such. Additionally, because count five included an element not involved in the other charges, it could also be charged as a separate crime, and double jeopardy did not apply.

The case was then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, where the defendant claimed his rights under the Fifth Amendment had been violated. The Supreme Court, in a unanimous decision, held that a defendant may be separately tried and sentenced for two similar crimes if each contains an element not present in the other.

If a trial court dismisses a case, after jeopardy has attached, based on procedural errors and defects, it becomes an absolute barrier against prosecuting the defendant again. For example, the prosecution must ensure the court in which the case has been filed, has jurisdiction over the matter. Failure to establish jurisdiction generally results in dismissal when the defendant objects. If the jury has already been chosen, or the hearings started, double jeopardy has attached. The defendant would be protected against subsequent prosecution on the same crime, as double jeopardy applies after dismissal.

United States v Scott

Police officer Scott was indicted on three counts of distribution of narcotics. During the trial, Scott asked that the case be dismissed, claiming his defense had been hindered by a pre-indictment delay. The court agreed and dismissed the first two counts, submitting the third count to the jury, which returned a verdict of not guilty.

The prosecution appealed the dismissal of the first two counts, but the appellate court ruled that re-trying these counts was barred by double jeopardy. The case was then heard by the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that double jeopardy does not protect an individual from subsequent prosecution if the case was dismissed on grounds that were not related to the defendant’s factual guilt or innocence.

Mistrials are granted in cases where circumstances make finishing the case impractical or impossible. Mistrials are also declared when jurors fail to reach a unanimous verdict. When this occurs, double jeopardy is not terminated if it occurs with the defendant’s consent. In other words, if a mistrial could be reasonably have been avoided, jeopardy is terminated, and the defendant cannot be retried. If the mistrial was declared by “manifest necessity,” jeopardy is not terminated, and the defendant may be retried.

United States v Josef Perez

In this case, the trial of Josef Perez for a capital offense ended in a hung jury, causing the judge to declare a mistrial. Perez’ attorney asserted that Perez had already been tried, and so was protected under the double jeopardy clause. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the declaration of a mistrial born of necessity, in this case, because the jury could not reach a verdict, did not prevent retrial on the same offense. Perez was ordered to remain in custody, pending a new trial on the original charges.

State of Georgia v James Arthur Williams

Retrials are not common as they can be very expensive for both the prosecution and the defendant. One notable case occurred in the 1980s, when James Williams, an historic preservationist and antiques dealer, was charged with the shooting death of his assistant and lover, Danny Hansford, in his Savannah, Georgia home. Williams was convicted at trial and sentenced to life in prison; however, his attorney, after the trial, received an anonymous copy of the police report showing that the arresting officer had provided contradictory testimony. The guilty judgment was overturned and Williams was re-tried.

The Georgia State Supreme Court found other irregularities and errors in the second trial, and the third trial ended in an 11:1 hung jury. The fourth trial was held in a different jurisdiction, in Augusta, Georgia, where the jury took only one hour to decide the killing was the result of self defense, and return a verdict of not guilty. This case of The State of Georgia v James Arthur Williams holds the record in the U.S. for the most number of mistrials, and became the subject of the 1995 book “Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil.”

A defendant has the right to appeal his conviction in certain circumstances. If the defendant does so, and the conviction is reversed due to insufficient evidence, further prosecution is not allowed. If the defendant appeals, and the conviction is reversed based on another factor, such as reversible error, the defendant can be retried. When a defendant appeals, they are also at risk for facing a harsher sentence if the case is retried. Most states however, prevent the prosecution from imposing a death sentence if the sentence was not issued in the first place.

Brown v Ohio

This case revolved around a defendant that stole a car from a parking lot in Cleveland, Ohio and was caught the next week in Wickliffe, Ohio. The defendant pleaded guilty to operating a vehicle without consent from the owner, also known as “joyriding,” in Wickliffe. He was then extradited to Cleveland where he was charged with auto theft for the same act. The defendant appealed to the Ohio Court of Appeals on the grounds that his rights under the Fifth Amendment had been violated. The appeals court agreed that, because both offenses arose from the same crime, jeopardy had attached, and the defendant could not be prosecuted again on that offense.

Strictly speaking, the double jeopardy clause of the Fifth Amendment only protects defendants against being prosecuted twice by the same government. This means that if a state prosecutes someone for a specific crime that violates statutes on both the state and federal levels, the defendant may still be subject to prosecution by the federal government for the exact same crime. The U.S. Supreme Court has upheld the dual sovereignty doctrine, in confirming that the government of the United States is a separate sovereign from any state government.

For example, a defendant may be tried by the state for murder, may be tried again by the federal government for a federal offense related to the same act, such as kidnapping or a civil rights violation. As a result of the 1992 Los Angeles race riots related to the beating of Rodney King, the officers were acquitted in their trial by the state of California. The federal government retried the officers for the violation of King’s civil rights. The double jeopardy clause did not apply, as the two separate governments may prosecute an individual for the same crime.